Online ExhibitS

— From The Durham Museum Photo Archive —

Brandeis Window Displays

Taking It To the Streets

Taking it to the streets

Have you heard the rumor that Nebraska is flat? Omaha’s early businessmen also disagreed. In fact, they believed it was not flat enough! Of the steep hills that plagued downtown, those on Douglas and Dodge Streets proved to be a thorn in the side of growth. City businessmen took it to the streets to bring the city to level ground.

All images are from the Bostwick Frohardt/KM3TV Collection.

Streets are the arteries that keep a city’s heart pumping. Good streets mean good business and health for that city. Early Omaha businessmen understood this and invested early in projects to improve thoroughfares. Of the steep hills that plagued downtown, those on Douglas and Dodge Streets proved to be a thorn in the side of growth. City businessmen took it to the streets to bring the city to a more level ground. Where first there was only dirt, packed down tightly, there soon came wooden planks, loose rock mixtures, and the crowning achievement of industrial growth, the concrete or asphalt paving we know today.

Douglas Street Leveling

Newspapers announced excitedly in December 1890 that the eyesore of downtown Omaha would soon be fixed. The “uncouth feature” they wrote about was a five-block stretch of Douglas Street. From 16th to 20th Streets the steepness of a hill went from 4 to 20 feet!

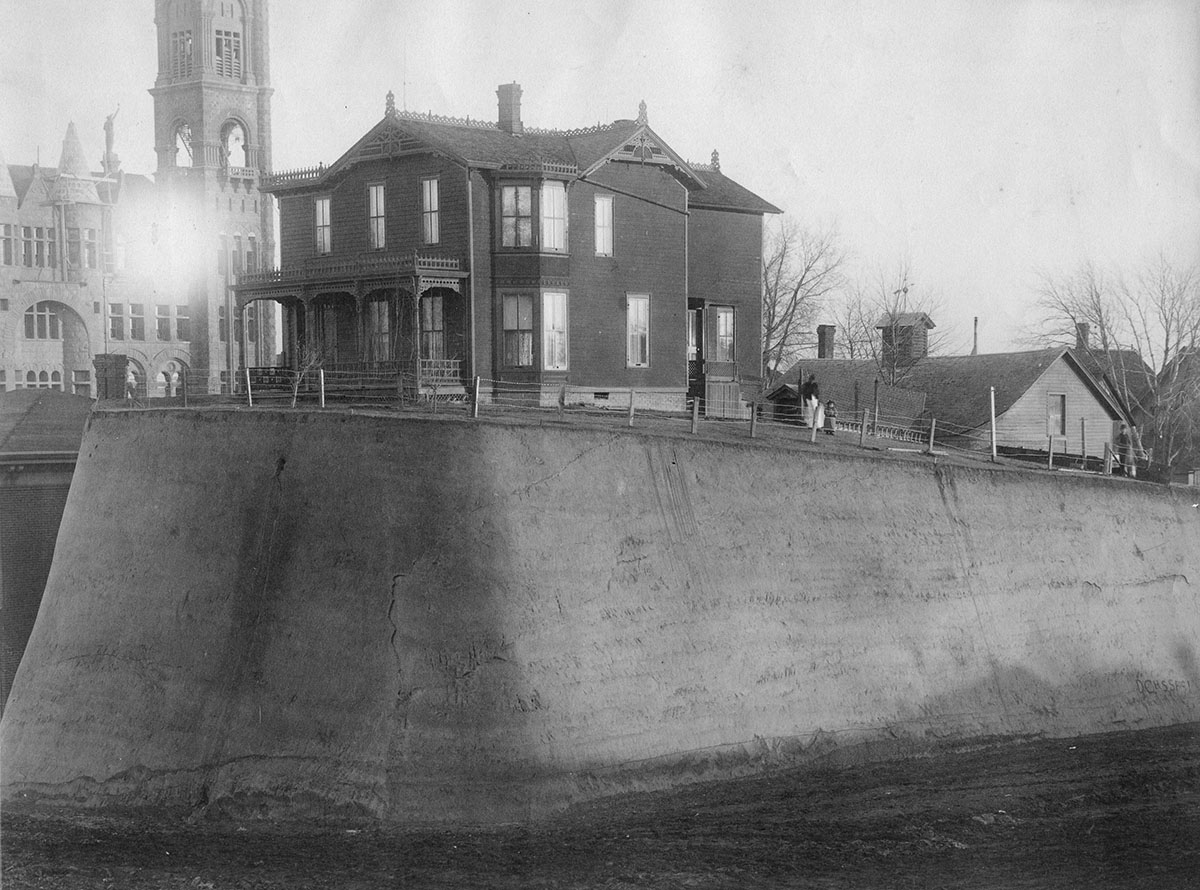

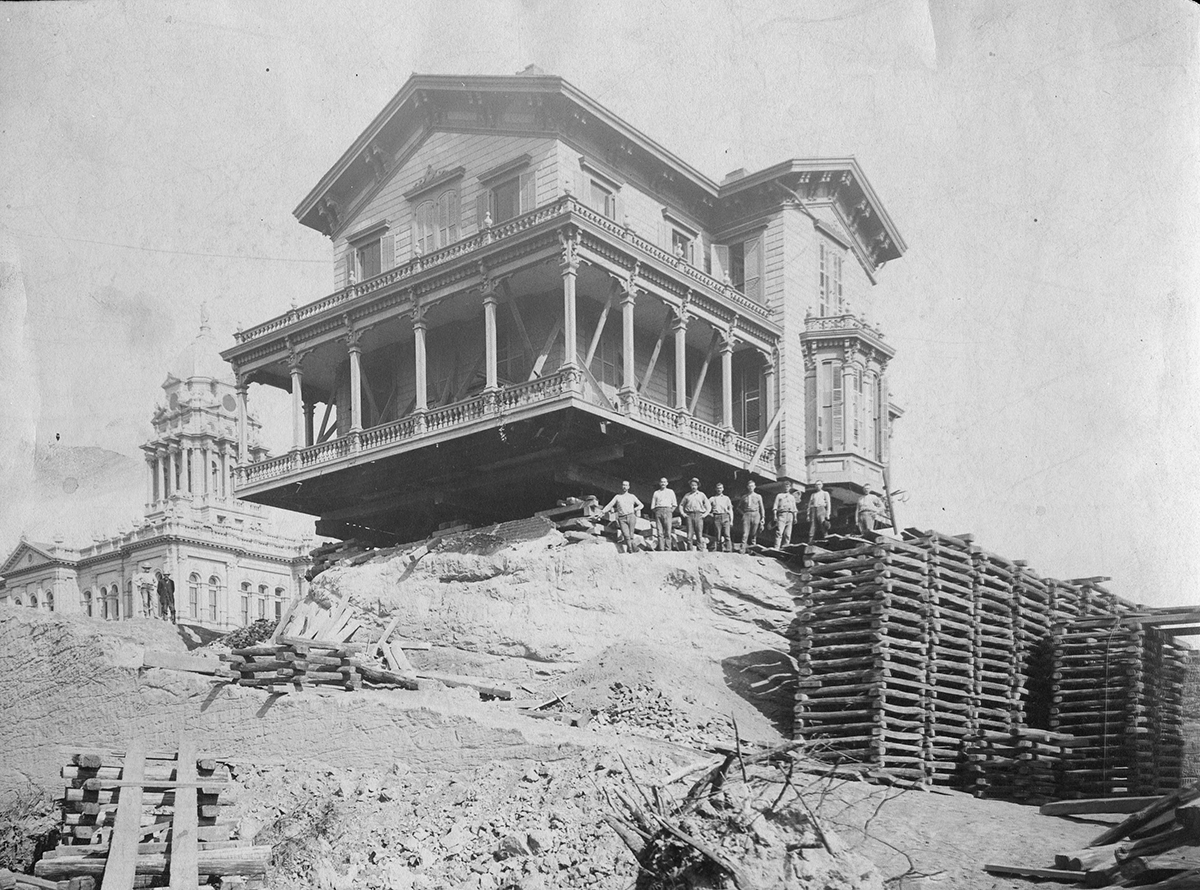

Altogether the project removed near 100,000 cubic feet of dirt. What would you do with that much dirt? They filled in the low-lying ponds of an old creek bed along Chicago, Davenport, and Dodge Streets. In this case, road improvement also contributed to health improvements. The ponds previously gave this area the nickname Diphtheria District. How much dirt is 100,000 cubic feet? These images give an idea of how much was removed under these homes that had to be brought to the new street level on 19th and Douglas Street.

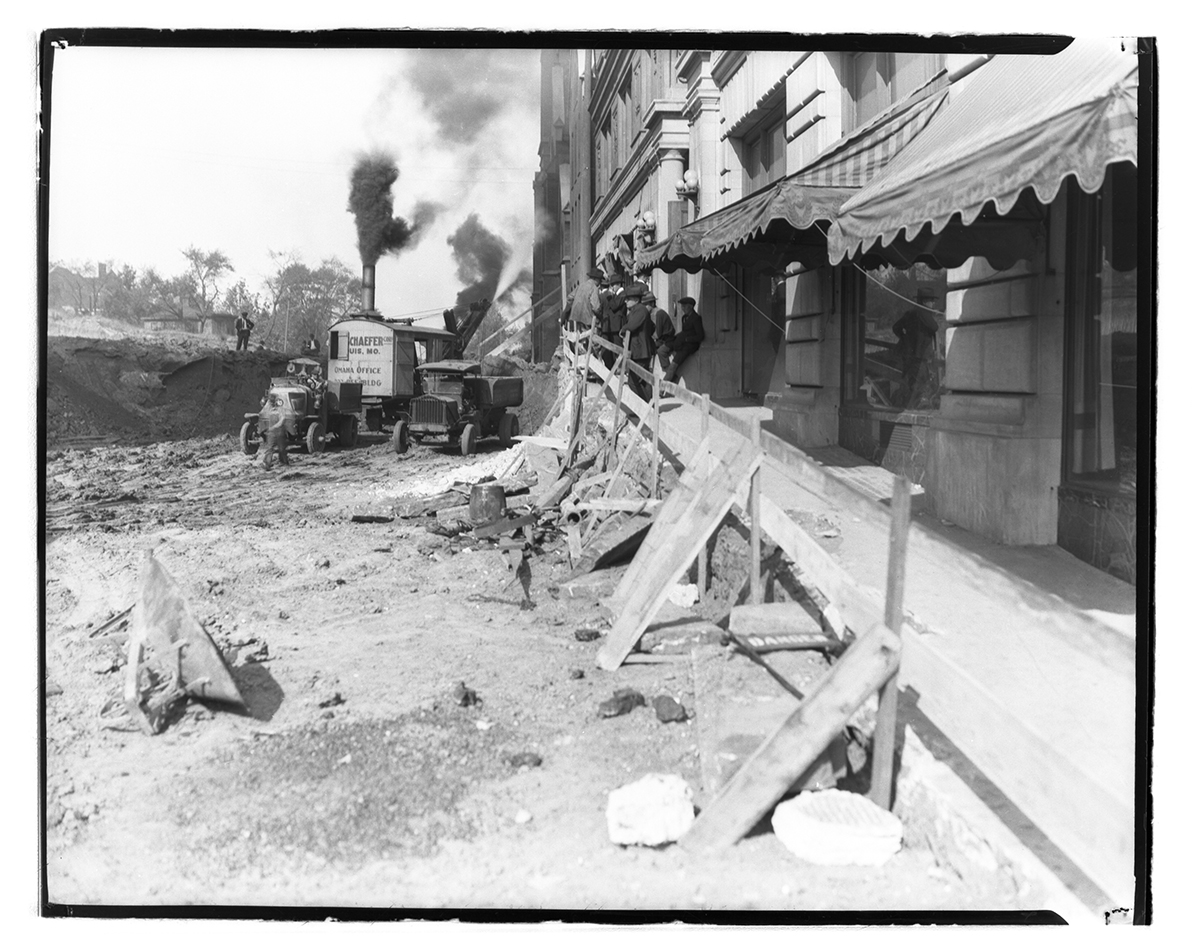

If any project deserved the saying “best-laid plans” this one is it. All the Dodge Street project foreman needed to do was dig and cart away over 350,000 cubic yards of dirt from 22nd to 17th Streets. How hard could that be? Turns out that dirt needed a specialized railway, traffic cops, its own attorney, a bridge, mules, diggers, and workmen, to tackle an incline of almost 25 feet between just two of the streets. It was one of the most expensive and detailed projects Omaha ever attempted.

St. mary’s

St. Mary’s Magdalene Church dropped over 20 feet in elevation along Dodge Street. If you drive past the intersection of 19th and Dodge Street now, you will see the original front entrance is now at the top of a fire escape. There is also a distinct difference in stone color for the lower floor walls that is visible on the outside. The expansion created a lower floor that allowed the original to become a second-floor balcony and produced a cathedral high-ceilinged effect inside.

It was not easy for those living downtown to endure the process. Residents along Dodge Street were mad, “maddened with insomnia.” On more than one occasion newspapers reported tenants along Dodge Street sued the contractors for disturbing their nights. 150 people petitioned a judge to limit working hours. The judge listened and restricted work to end at 9PM and begin no earlier than 6:45AM but it did not stay that way. To get the work done more efficiently most workdays began at 6AM and ended at 10PM.

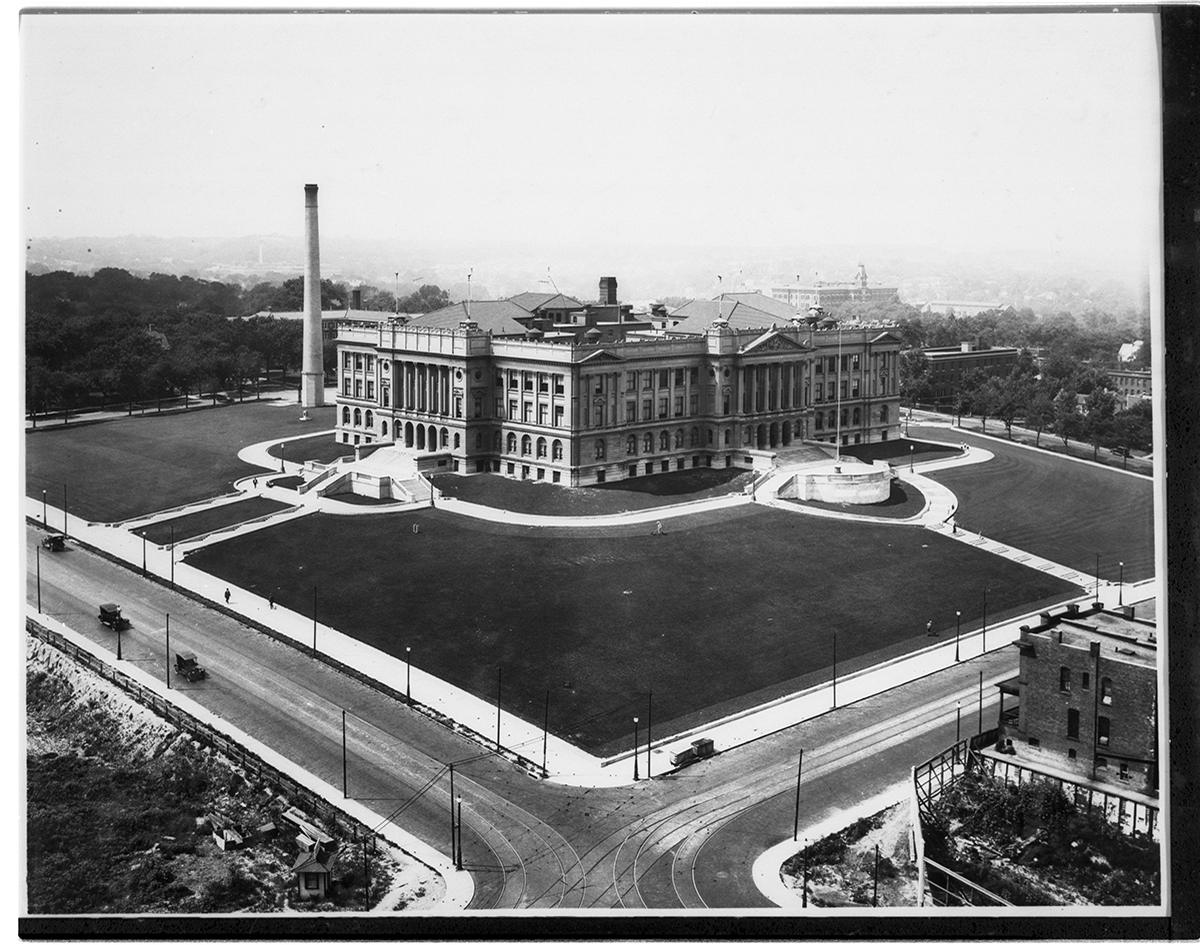

central high

In the fight over construction noise Central High School was on the side of the contractors. The grading created horrible driving conditions around the school, and it was in the best interest of the students for it to be done as soon as possible. Work on improvements took long enough that there were serious jokes in the newspapers about students needing to learn to parachute.

The school decided it liked being on a hill and after a 5-foot cut, sloped its sides down to meet the new grades. Other improvements during the construction created walking paths that circled the school and met the streets on each side.

sidewalks: finishing touches

On average the construction work was done in two shifts with hours extending from 6 AM – 10 PM. Grading ended in November 1920, but street paving and sidewalk installation continued for the next six months. The lack of sidewalks was a major issue for those who worked downtown, and many businesses ended up paying for them individually rather than waiting for the city. In total, the grading of Dodge Street cost $1,125,000 which was a cost shared by both the city and private owners downtown. That is roughly $14.4 million today.

The Durham Museum Photo Archive contains over 1 million images that document the fascinating history of Omaha from its early days as a young frontier town to a unique and sophisticated city.